Tick Control and Management in Beef Cattle

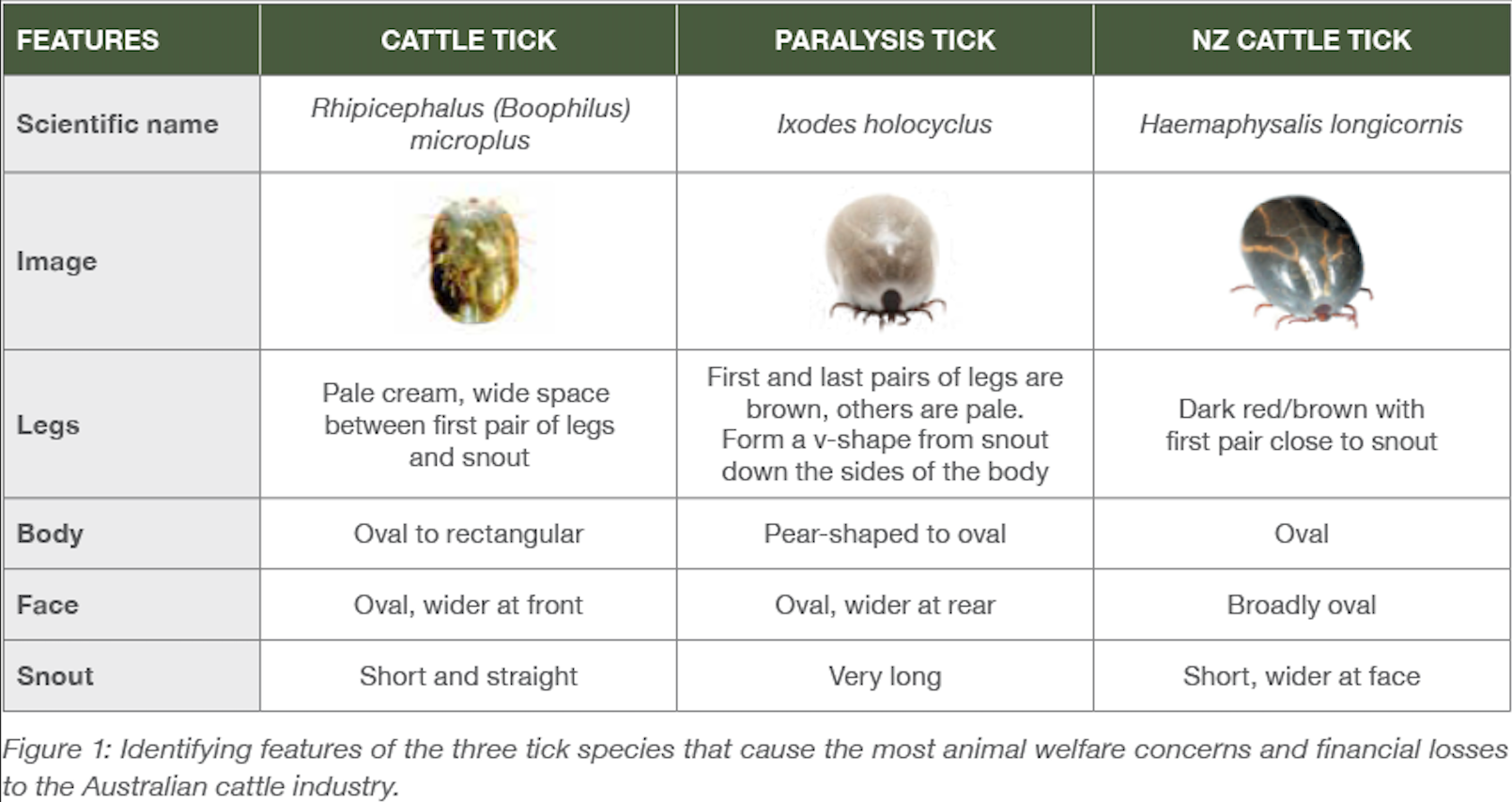

The Cattle Tick, Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) australis, the Paralysis Tick, Ixodes holocyclus and the New Zealand Cattle Tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis are the three most common tick species affecting cattle in Australia. These blood-feeding ectoparasites can cause serious welfare implications and economic loss. To ensure effective control and management, it’s important to recognize the differences between these tick species as shown in Figure 1 below.

This article will focus on the tick that causes the most financial impact in Australia – the cattle tick. Cattle tick are found widely in northern Australia from northern parts of Western Australia and the Northern Territory, eastern and northern regions of Queensland and into northern New South Wales. The distribution of cattle ticks in QLD is limited by legislative restriction zones, which declare areas either tick infested or tick-free.

Cattle Tick Lifecycle

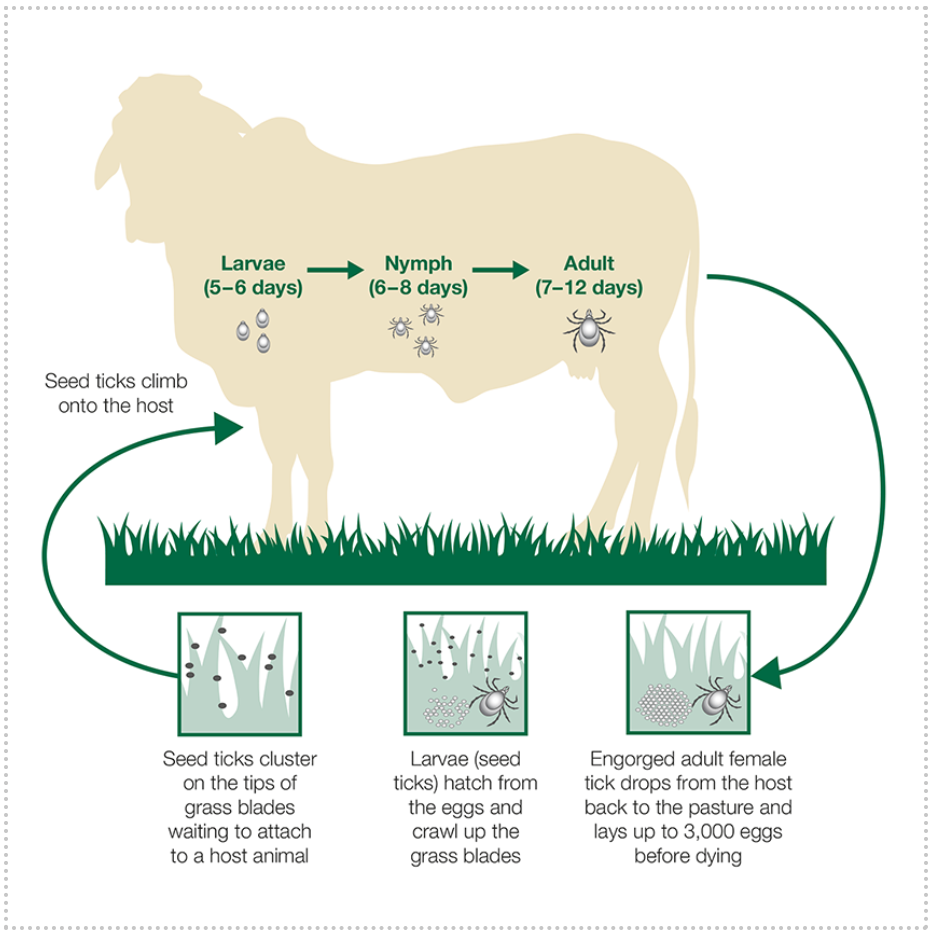

Cattle ticks are single host ticks, meaning the larval, nymph and adult stages develop and feed on the same host. They have two stages of their lifecycle: the parasitic stage and the non-parasitic stage.

The parasitic stage takes approximately 21 days to complete; the tick develops (moults) from larvae (seed tick) into a nymph, and then an adult. Female adults feed for about a week (7 to 12 days) before engorging and dropping off the host to return to the pasture. During the non-parasitic stage on pasture, female adults lay up to 3000 eggs and then die. The eggs hatch (under favourable conditions 15°C to 40°C) to become larvae that climb up the pasture sward, where they wait to be picked up by a host animal or they die off. Survival during the non-parasitic stage can vary from 2 to 9 months, depending on the time of the year, geographic location and seasonal conditions. Survival is adversely affected by extremes in temperature and humidity.

The Impact of Cattle Tick

Cattle ticks are recognised as the second costliest disease to the Australian cattle industry, costing an estimated $134.2 million per year in lost production and treatment costs.1 Infestations can cause substantial welfare implications and economic losses arising from tick worry; a generalised state of unease and stress in affected cattle. Calves and cattle in poor body condition are most susceptible to the associated stress. Cattle can suffer from anaemia (a deficiency of red blood cells or of haemoglobin in the blood) from loss of blood, manifesting as lethargy, lack of appetite and exercise intolerance (cattle lag behind the mob), and can ultimately result in death.

Cattle ticks are vectors (carriers) of three blood-borne diseases – Anaplasma marginale (anaplasmosis), Babesia bovis and Babesia bigemina (babesiosis or ‘red water’). Collectively these diseases are known as ‘tick fever’. Tick fever can cause many clinical signs including lethargy, weakness, loss of appetite, jaundice (yellowing of skin and whites of the eyes), neurological signs, abortion, and blood loss in urine (giving rise to the name ‘red water’).

Significant loss in liveweight gain, and milk production and quality can be associated with cattle tick infestation. It has been reported that just one tick can reduce weight gain by 1 g/head/day or milk production by 8.9 mL/head/day.2 Assuming an ‘average’ burden of 50 ticks per head, that equates to 1.5 kg of lost liveweight gain worth $6.15/head^ or 13.5 litres of lost milk production every 30 days.

^Assumptions: One tick reduces weight gain by 1 g/day x 30 days x $4.10/kg liveweight. One tick reduces milk production by 9mLday x 50 ticks x 30 days.

Controlling and Managing Cattle Tick

Controlling cattle ticks and the diseases associated with them remains a challenge for cattle producers. Both non-chemical and chemical control options are recommended and should be used in an integrated manner tailored to an enterprise.

Non-chemical control options include breeding tick resistant cattle by having higher Bos indicus content for a greater level of genetic resistance to ticks; vaccination to provide life-long immunity against tick fever, and strategic pasture management to help break the life cycle and reduce the tick burden on pasture.

Chemical treatments using acaricides (chemicals that kill ticks) remain the most common tool for managing ticks on cattle. A strategic control program should aim to reduce the buildup of tick populations on pastures and cattle before the annual peak, and curative treatments used to reduce existing tick burdens. As with all parasiticides, these treatment options should be used strategically to prolong the efficacy of the actives currently available and help minimise resistance development.

Acaricides can be applied in various ways, such as cattle dips or sprays (e.g. Bayticol™ Dip and Spray), by backline pour-on (e.g. Acatak™ Duostar Pour-On) or by injection (e.g. Bomectin™ Injection). Any treatment option should be considered based on their chemical class and resistance status, protection period, management practices and any residue considerations. It is also important to ensure that all new stock are inspected, treated and quarantined before introduction to the herd.

These management strategies can achieve significant economic benefits via improved liveweight gain and milk production and help to address the welfare concerns with tick infestations on cattle.

Interested in learning more about tick management and control solutions for your operation? Contact your local Elanco representative today.

1. Shephard et al. (2022) B.AHE.0327: Priority list of endemic diseases for the red meat industry — 2022 update. MLA.

2. Jonsson, N.N. et al. (1998). Production effects of cattle tick (Boophilus microplus) infestation of high yielding dairy cows. Vet. Parasitol. 78: 65–77.